Last year my family and I began a new tradition. Instead of eating a Passover Seder meal and having a separate Seder plate, we combined the two, incorporating each part of the traditional (and newer egalitarian) Passover plate components into the meal itself. Because so much of my personal Jewishness is enacted in my relationship with the environment, social justice, and--most of all--food, it only makes sense to translate the ritual objects of the Jewish spring holiday into a satisfying meal shared with people I love. Some of you may know that I'm finishing up my bachelors' in Religious Studies, and writing my thesis on ethical and sustainable kosher food movements, so I spend a LOT of my time thinking about the meanings of food, both in relationship to Jewish tradition and to my own (still developing) value system. So here's my idiosyncratic, hodge-podge of a Seder plate-turned-meal. And, most warmly, Chag Pesach Sameach!

So, quick background for the unfamiliar (Pesach in 140 characters!):

Jews: slaves in Egypt, were liberated, ate flat bread, sacrificed goats. Today, we don't eat chametz*, eat symbolic foods, & tell the story.

*"Chametz" includes anything made from wheat, rye, barley, oats and spelt that has not been completely cooked within 18 minutes after coming into contact with water. Some Jews also avoid rice, corn, peanuts, and legumes as if they were chametz. All of these items are commonly used to make bread, so the use of them was prohibited to avoid any confusion. Such additional items are referred to as "kitniyot." (Ok, so I love how that explanation was longer than the first...)

Aside from the ubiquitous matzah, my table was full of new and old Passover dishes and symbolic foods. At last year's Hazon food conference (a weekend of exploring the intersection of Jewish life and contemporary food issues), I had the pleasure of meeting Roberta and Robert Kalechofsky, the uncontested Queen and King of Jewish vegetarianism and animal rights. They are responsible for creating the standard vegetarian haggadah, Haggadah for the Liberated Lamb, in which the replace the lamb shank with:

"Olives, grapes, and grains of unfermented barley, which symbolize the commandments of compassion for the oppressed, to be found in the Bible. We use olives to commemorate the commandment to leave the second shaking of the olive trees for the poor, we use grapes to commemorate the commandment to leave the second shaking of the grapevines for the poor (Deuteronomy 24:20), and we use grains of unfermented barley (or other unleavened or unfermented grains), to commemorate the commandment not to muzzle the ox when it treads out the corn in the fields (Deuteronomy 25:4), in other words, to recognize the natural appetites of the animal and not interfere with them. This commandment is considered to be the oldest extant concept of 'animal rights,' and enshrines the dignity and rights of the animal."

I'm not a strict vegetarian (though that's a post for another day) but I love this idea, and while it may not be traditional Seder fare, I'm a firm believer in the adaptability of Jewish cultural traditions to progressive interpretations.

Another option for the vegetarian replacement of the lamb shank is a beet: the blood-red color recalls the Pesach sacrifice, though Cynthia Baker of the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Cornell University offers a different explanation for the beet.

"What is the meaning of the beet? It is here to remind us of an incident that occurred in 1945, when women slave laborers in Buchenwald concentration camp changed a negative definition to a positive one. 'It hit me suddenly that the Haggadah could have been written for us. If I only changed the tense from past to present, it was written about us.... At this time, the scene in the barracks was bad, there was really fighting, cursing, and yelling... so when I asked the women to be quiet it was like a miracle, this absolute silence in the barracks. I started the seder by asking why is this night different. And I said that every night we quarrel and we fight and tonight we remember. There were close to a thousand women there. I picked up the slice of sugar beet and I said, this is the bread of our suffering.... And then we made a vow that if we survived, a beet was going to be on our seder table.'"

I decided to incorporate the beets into my main dish, a roasted curry beet and carrot casserole:

One of the best parts of the Passover meal is Charoset, a mix of fruit, wine, spices and nuts that represents the straw and clay which the Jewish slaves used to construct Egyptian buildings. One of my dinner guests is a huge Charoset fan, so I kept this pretty traditional. I did choose to cook my apples down with cinnamon, then added currants, pecans, red wine, and honey.

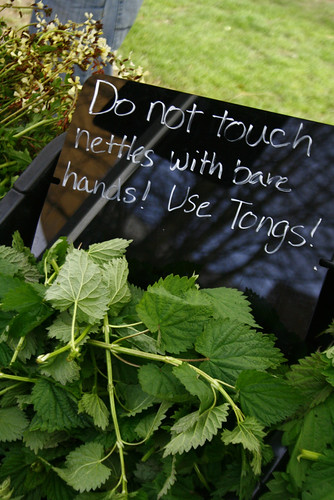

For the bitter herbs, Maror and chazeret, which represent the bitterness and harshness of slavery, I used the traditional horseradish and romaine lettuce to make a salad. The dressing was made of olive oil, yogurt, horseradish, apple cider vinegar, and salt. Is it wrong that the "bitterness of slavery" turned out to be really, really tasty?

The Beitzah, or roasted egg, on the Seder plate was replaced with deviled eggs, simply because I LOVE DEVILED EGGS. I'm a total traditionalist, just mayo and eggs, but I go crazy for them. The egg represents a lot of different things, and many people have a different interpretation of it's place at the Seder. It may represent the korban chagigah, or festival sacrifice, prepared at the Temple, but I usually talk up the connection between Pesach and earlier pagan holidays of springtime, fertility, and renewal:

Then there's the karpas, any vegetable other than the bitter herbs--though parsley is the standard--that is dipped in salt water representing the tears of oppression. This is typically the first thing eaten at a Seder after kiddush over wine, when bread would usually be consumed, prompting the four questions of why the first night of Passover is different from other nights. I turned the parsley and salt water into a tabouli (sans grains). I make so much tabouli, this was a no-brainer. I call it kitchen-sink tabouli, because I throw in anything I've got in the fridge--here I used cucumbers, tomatoes, red onion, Israeli feta, and toasted walnuts, with a dressing of olive oil, lemon, and plenty of salt. Tabouli should be salty!

Lastly, to connect the Passover holiday to the beginning of Spring, I roasted up my favorite vegetables from the market this time of year: asparagus and raab. I used collard raab here, and simply tossed the veggies in olive oil and salt and put in under the broiler until tender. So good!

I also have an orange on my Seder table, representing the fruitfulness of a Judaism that celebrates the inclusion of all Jews: women, the GLBT community, and patrilineal Jews. The tradition comes from Jewish scholar Susanna Heschel, and you can read about the evolution of this symbolism here.

So that's how I celebrate, with good wine, good food, good friends, and new traditions as well as old. If you celebrate Passover, how do you explain the individual parts of the Seder plate? If you're making Easter Dinner instead, what new and old traditions do you incorporate? However you celebrate this season, enjoy the Spring (with it's crazy weather here in Portland) and the great foods that come with it.

Eat Well!